In honor of Mental Health Awareness Month, we are inviting one guest writer a week in the month of May to write about their perspectives on mental health. Today’s guest blog post comes from Debi Strong who currently has an art exhibit, 365 Days of Gratitude, that is touring several venues around the country. Her post covers her struggles with life-long depression and how gratitude and art have helped her manage her depression as well as inspire others. Thank you, Debi, for sharing with us at rtor.org. -Veronique Hoebeke, Associate Editor

On March 20, 2012, much to my dismay, I was brought back to consciousness in the ER of my local hospital. At that time, gratitude was the last thing on my mind. Instead, I felt desperation, shame, and horror as I became aware that I hadn’t died. There was also an overwhelming feeling of failure when I realized that I couldn’t even succeed at killing myself. It would be a long time before I felt grateful for anything.

Several weeks earlier, I had spent hours in the same ER, voluntarily admitting myself to Pathways Treatment Center, the local acute psychiatric care facility. Hospitalization was my last hope for help after a lifelong struggle with depression. Nine days later, with no significant difference that I could feel, I was released. I kept my follow-up appointment with my psychiatrist and I was stunned by what I heard her say. She told me that I had tried everything in the way of antidepressants and therapy, and that perhaps the best course of treatment was a vitamin regime. I looked at her in disbelief. I already had tried nutrition, supplements, exercise, self-help courses, a three-week intensive in Utah, read almost everything written about depression, and seen too many therapists to count since I was a child. My last bit of hope evaporated, and I left her office with the intention to end it all the next day.

The following morning, in somewhat of a “depression trance,” I kissed my daughter good-bye as I dropped her off at school and walked my dogs for the last time. I bought the shampoo my daughter had asked for, drove home, straightened up the house, and wrote a brief note. I was too sad to write more than “I’m sorry. Good bye. I love you.” Then I swallowed all the narcotic painkillers that I had saved up from various surgeries over the years. I carefully took a few at a time over an hour to make sure I didn’t vomit them up. I didn’t choose this method randomly as I had a career in law enforcement and had seen many suicides and photographed and processed the scenes. Overdoses were infinitely “cleaner” and less visually traumatic to surviving family members than gunshot head wounds. I wanted to spare my family that vision.

I knew no one would be home for at least eight hours. By then I would be dead and everyone would be better off. Sure, they’d be sad for awhile, but then their lives would be much improved. My husband would find a better wife, my daughters would adore her, no one would have to worry about me anymore. It was all for the best. I would finally be at peace. No more agony.

Obviously, my plan didn’t work. My family came home; I was airlifted to the hospital, and re-admitted to Pathways. This time, I was told, due to the limitations of their in-patient program, I would be sent to the state mental health institution within a week –or, by staff approval, to another in-patient facility if my family wished.

As it turned out, my husband enlisted my sister’s help, and after an internet search for the Top-Ranked Psychiatric Hospitals list on the U.S. News and World Report site, and a series of frantic phone calls, I was admitted to The Menninger Clinic in Houston, Texas. Two days later I arrived in Houston, still feeling humiliated and ashamed. As I walked towards the admissions desk, I figured this was my last resort. If this didn’t work, I would find a more definitive way to end my life. To further illustrate the depth of my long-term despair, in 2009, when I had been diagnosed with breast cancer and underwent a double mastectomy, I had been almost giddy with relief; I could put up a good fight but die anyway, and it wouldn’t be my fault! Surviving cancer didn’t make me happy — it only made me more depressed.

From Patient to Teacher

I spent nine weeks at The Menninger Clinic and in that time, I learned more about myself, depression, and suicidality than I had during the rest of my life. From sun-up to bedtime, there were classes, individual therapy sessions, group therapy, a variety of more loosely structured activities and the most integrated support network of peers and professionals that I could ever have imagined. In fact, it was the closest thing to a family that I had ever experienced, and in many ways I still consider that time at Menninger as the best nine weeks of my life. (That can be an embarrassing fact to admit to people: the best time of my life was spent at a psychiatric hospital. But it’s true!)

During that time, I learned that dealing with depression requires a multi-faceted approach. There is no “magic pill.” What I have found since then is that managing this disease generally requires five things: medication, psychotherapy, a variety of coping skills (e.g. CBT and DBT), real support from people who “get it” and the willingness to adhere to a personal healing program while learning to trust the process.

When it was time for me to leave, I was terrified. Although I felt capable of managing my depression there, I wasn’t sure if I was capable of doing it on “the outside”. Even though I loved my family, the thought of going back to the same environment that I had come from was nauseatingly scary. It was extremely hard going from so much support to very little. It seemed like one day I was at a place where everyone spoke the same language, and the next day I was at a place where I had to teach that language to others.

But I had changed and instead of getting depressed, I took action. When I couldn’t find a local support group for people with depression, I wrote to the CEO of our medical center to explain my situation and detail the community-wide need. She referred me to the clinical supervisor at the same acute facility where I had started out. Long story short, in November, 2012 I began facilitating an outpatient depression support group at Pathways — I had come full circle at that facility, from patient to teacher. And as of 2014, I also began sharing my story and experiences in a weekly session for in-patients.

In my ongoing efforts to give back to my community, and to other people who are suffering as I have, I have become a local spokesperson/”poster child” for information about suicide and depression. I continue to “come out” in the newspapers and show up on the internet in a continuing effort to de-stigmatize these issues.

The Power of Art and Gratitude

Throughout the past four years, I have been vigilant not only about maintaining my own wellness program, but also about seeking other ways to enhance my efforts, keeping an eye on the latest articles regarding advances in neurological, psychological, and behavioral research. One of my most favorite researchers is Dr. Brené Brown, from the University of Houston. I had watched her wildly popular TED talk, “The Power of Vulnerability,” shortly after returning home in 2012, and started reading her books and sharing her wisdom both with my group and my friends.

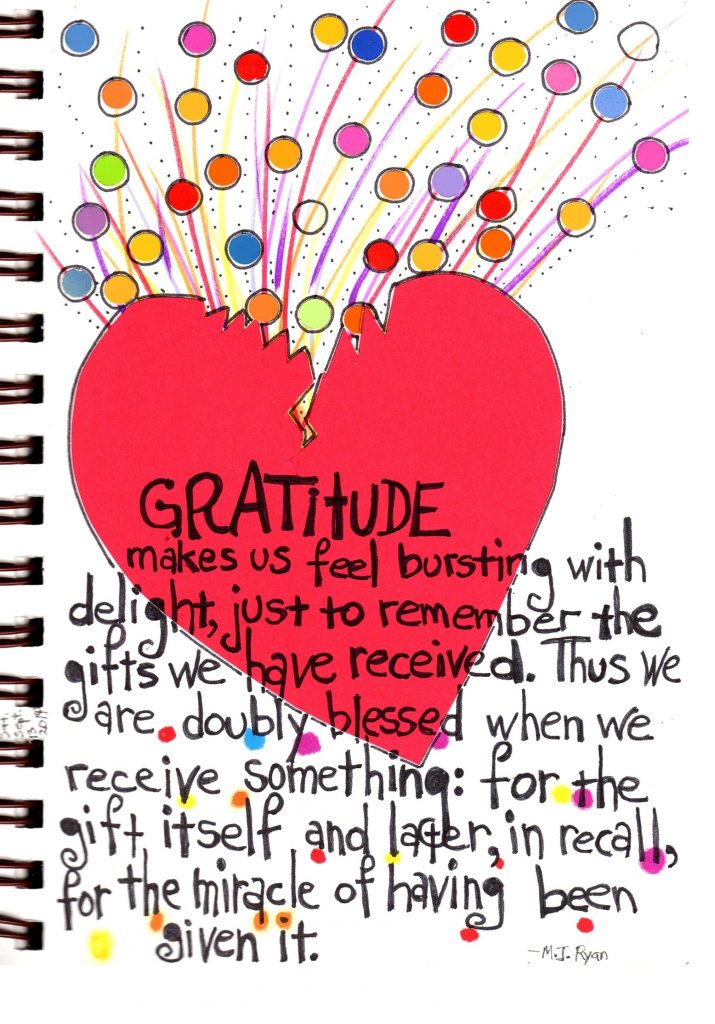

In the Fall of 2013, when I discovered she was going to teach an online art journaling course based on her book, “The Gifts of Imperfection,” I signed up immediately. Although I had been a productive mixed-media artist for years, I had never done anything like this. During the course we studied the connection between a gratitude practice and joy. It wasn’t a new concept to me, and I absolutely believed it made sense, but after years of trying to keep a daily gratitude list or journal I kept failing miserably. However, I ended up enjoying e-course so much that I didn’t want it to end.

And then an interesting thing happened, in the way that synchronous events often do. On Thanksgiving Day, I just happened to watch a TED talk by Brother David Steindl-Rast, a Benedictine monk and interfaith scholar. When I went to his website, www.gratefulness.org, and saw there was a link for a Word for the Day, I signed up and for some reason decided to commit to creating an art journal page-a-day based on the quote I received from the site, for a year — beginning that day, Thanksgiving, 2013. At the time, it seemed like a great idea!

The reality was significantly more challenging. First, it took time out of an already busy schedule. Second, it required consistent self-discipline in that whether I was in town or out, sick or well, feeling happy or sad, I still had to create that page–every single day. And third, I found very quickly that I also had to give up any sense of perfectionism, because I simply couldn’t spend endless hours each day making something “perfect.” I also decided that I would not give myself the option of tearing out pages and starting over. A bonus, however, was that while working on each piece I had to go over and over the words in my mind, setting them more firmly in my consciousness than had I simply read them each day.

The daily commitment to this practice was difficult. In fact, during the last three weeks of the project I spent my days with my ailing uncle in the ICU of a Colorado hospital. Many times I was overwhelmed by life in general, but I kept going, and it did pay off. I felt much better while I was journaling, and the practice was worth the effort. I succeeded in finishing my project, fulfilling my commitment to myself by creatively practicing daily gratitude. And I had five-and-a-half journals filled with cool art and wise sayings to show for it. An artist friend, who had been watching the process, subsequently kept encouraging me to print all 365 days and exhibit them as an art show.

I finally succumbed to her pressure and in September, 2015, “365 Days of Gratitude — An Art Journaling Project,” was installed at the Bigfork Museum of Arts & Culture, along with a brief account of my story. The positive community reaction was amazing and gratifying.

At the moment, the exhibit is at The Menninger Clinic, and when it returns to Montana, the regional medical center is going to install it and it will remain there for six months.

In the end, I have to agree with the researchers: a gratitude practice can increase one’s ability to experience joy and happiness. I also heartily encourage others to try combining art with gratitude. After all, who doesn’t need a bit more joy in their life?

Debi Strong

Subscribe to our e-newsletter for more mental health and wellness articles like this one.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

Recommended for You

- Veterans and Addiction Recovery: How Families Can Support Their Service Member’s Healing Journey - July 14, 2025

- Trauma-Aware Yoga: A Gentle Path to Healing and Recovery - July 10, 2025

- Why Eating Disorders in Men Are Often Missed - July 3, 2025

Thank you Debi for sharing your compelling and inspiring story with rtor. I was very moved by your transformation and particularly love the power of gratitude and art. I hope that your beautifully expressive and dynamic pieces come to the Northeast.

Thanks, Denise! I’d love to see that happen as well :-).

You have creative ideas and I am 14 years old and I am a artist and a lot of people I don’t know saw my pictures and they said they love my art. And you have a artistic creative mind.