For years, I lived in the shadow of abusive relationships even after they ended. Most of the time, I was a prisoner of my thoughts and emotions. The scars were not visible, and they ran deep. For a long time, I felt I would never escape the emotional and mental pain of it all. Along […]

Our Latest Blogs

Living with a disability or chronic illness is more than challenging on the body—it’s challenging on the mind. With poor health and disability come stress and worry. Healthcare can be expensive, and much of society can be inaccessible. Worries can lead to anxiety and depression. According to the CDC adults with disabilities report experiencing frequent […]

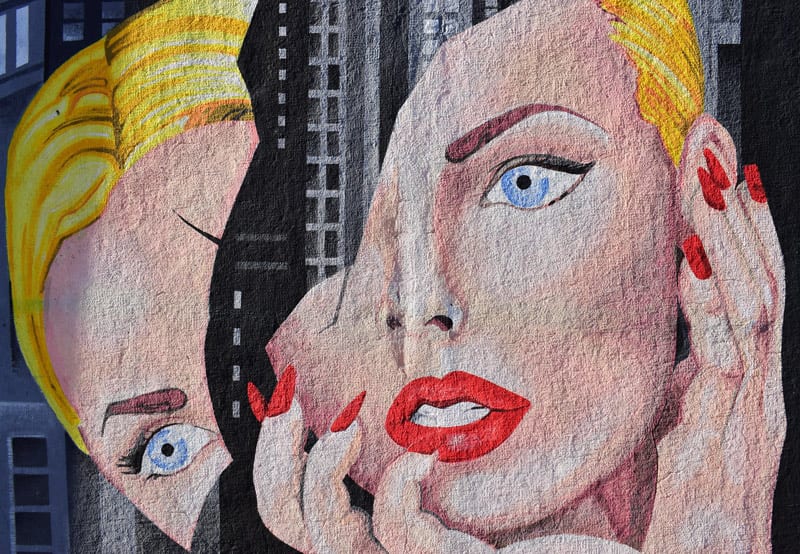

Hello, dear readers. Today, I want to share my personal journey of battling body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). For 26 years, I lived in a body I found disgusting, believing I was unattractive and flawed. The constant comparisons to others left me feeling inadequate and isolated. However, through perseverance, support, and professional help, I have started […]

Coping with mental illness has never been easy. There’s a lot involved, including your commitment to mental wellness goals and outside factors such as stigma. However, with the right routine, tools, and guidelines, you can cope with mental illness. You may wonder what those guidelines are. My battle with mental illness went on for about […]

My mom is a wonderful mother. She’s kind, loves classic rock, has funny stories—and she loves me. I know that. I have always known that. Ever since I can remember, I wanted to be understanding of her problem. I saw her drinking and began to justify how normal it was. Resentment was there, but it […]

In 1987 when I was 22 years old, I was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Scared and alone, I had no role models to guide me. Hospitalized and given pills, I was sent out into the world to find my way without a map. In June 2000, I obtained a Master’s in Library and Information Science. That […]

I did not inherit Kim Kardashian’s butt. I inherited my father’s rear end – flat and wide. I passed this rear end down to one of our girls. The other lucked out and inherited her father’s butt – a cute pop-out affair from years of squats and deadlifts. Perfect for twerking, but her father and […]

For the entirety of my life, I have tried to do right in everything and by everyone. For the first time this past year, I questioned my capacity to do that and, in turn, questioned everything that I thought I knew about myself. Since adolescence, I have prided myself upon my successes, resiliency, willingness to […]

About 15 years ago, I told my therapist about the social isolation I was struggling with. It had been a few years since my mental breakdown, and I didn’t want to be seen by my friends until I felt better. I didn’t know what to say to them, so I avoided them. I was too […]

I thought I was happy with who I became, but the repercussions didn’t agree I grew up in a small town located in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. The school I attended was K-12, with all of us located in one building. The entirety of my graduating class was 20 people, each of whom […]

Content Advisory: This guest blog post contains frank language about sex. This is not something I’ve admitted publicly or even to more than a handful of close friends. I have had OCD (obsessive-compulsive disorder) since I can remember. It started as constant handwashing (whenever I touched someone) and obsessively checking that my door was locked. […]

There’s a lot that’s unknown about mental health disorders. They are widely misunderstood. They carry stigmas, are joked about, and lack proper research. You may ask yourself: Why is that? Many people struggle with their mental health. Research shows that 20.6% of U.S. adults deal with mental illness. This translates to one in five adults […]

Being depressed, then getting out of it, then falling into it again—does that sound familiar? If you are a depression survivor, most likely you know how it feels. It may feel like you are walking on a never-ending path or a journey that keeps dragging you to the same point over and over again. But […]

College drop-out. At the height of my anxiety, depression, and inner turmoil, I struggled to take care of myself, let alone do something as demanding as learning and participating in academics. Despite having gone to see therapists, cycling through medications, and buying a shelf’s worth of self-help books, I was floundering, barely able to keep […]

The nature of a traumatic event is not completely generalizable and varies from person to person. What constitutes trauma for one person does not necessarily translate to trauma for another. Several factors can determine how a person experiences crisis or otherwise stressful life events. Pain tolerance is not merely an attribute of physical hurt. Emotional […]

Ever-increasing urbanization and overpopulation are inevitable in today’s world. Such phenomena can lower ordinary people’s living standards due to the reduction of living spaces, increasing risks of interpersonal conflicts, and loss of privacy. For individuals who experience social anxiety disorder (SAD), living in a collective space can be far more challenging. I have been suffering […]

I can still remember the first time it hit me. I was in high school. As my teacher handed my exam back to me with a failing grade printed on it, I felt nothing. What once would elicit an emotional response in me now didn’t even justify a second glance. It wasn’t anger. It wasn’t […]

I am 6 years old. My dad and mom are fighting—this time over a field trip that I missed because my parents slept in too late. The screaming starts. I go into the kitchen to see what the commotion is about. I hear my dad yell at my mom and then push her into the […]

For the ten millionth time, I recently ended up in the emergency department (ED) for shortness of breath, chest pains, and nausea. What I didn’t realize is that these symptoms are also symptoms of a panic attack or anxiety. Panic attacks can come on unexpectedly and manifest in physical symptoms. This is something that has […]

My dad was a brilliant, hardworking attorney with a great sense of humor and loads of charisma. My dad was also an alcoholic. In many ways, I followed his footsteps. I was 13 when I started working in his law office, and I went to college and pursued a career as an attorney. I worked […]

I am here to say that there is much hope for people who have a mental illness. From 1990 through 2001, I was hospitalized four times. Most of the recurring visits were due to my perception that the regular consumption of medicine would put me into a class of people who suffer from stigmatization. Mostly […]

Depression is a serious mental health condition that is characterized by feelings of sadness and hopelessness. If you’re going through depression, you might wonder how long it will last. While there is no average for how long it can take to overcome depression, it’s not uncommon for feelings of hopelessness to last several months. In […]

My life with bipolar disorder II has included six periods of success and six periods of failure. The worst began in 1980 when I was 42 years old. I had purchased a small guest ranch in Wyoming with the woman I loved. The ranch, which faced the Continental Divide at 8,000 feet, was to be […]

At 3 am on January 18, 2018, a cold winter’s night when most everyone was fast asleep, my wife and I were wide awake. Our then 17-year-old daughter, Audrey, was about to be abruptly woken up and transported by a third party to a wilderness therapy program. She had no idea this was about to […]

How cannabis abuse aggravated my borderline personality disorder to the point of medical intervention. Marijuana is a controversial topic when it comes to mental health. I have friends who have been self-medicating for years, insisting that weed cures their anxiety and helps them cope with their depression. I also have friends who refuse to touch […]

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the fact that toilet paper, bottled water, and disinfectant wipes sold out nearly everywhere was common knowledge. What you may not know is that in some communities baking yeast was just as hard to find. During a time of complete and utter panic, many people turned to baking […]

Today’s world is a world of constant controversy. No one seems to agree—on anything. No wonder anxiety plagues so many of us! I often wonder if I will ever get better—less depressed, less anxious, less paranoid, with this current state of things. It reminds me that although I was personally diagnosed with bipolar disorder, depression, […]

“Depression is treatable.” That’s what the brochures and websites always say. “Help is available,” they say. And it is, for most people. But for some people, treatment isn’t so simple. How long does depression typically last? According to Harvard Health, depression can last any duration, but the average for untreated depression is “several months”—suggesting people […]

I had a trauma-filled childhood with a single, alcoholic, abusive mother. She belittled me, neglected me, and really acted like she hated me. She said she wished I wasn’t born, called me a slut and too fat or too thin. Nothing was good enough for her, except her alcohol. I could never make her happy, no […]

I glanced down at the speedometer and realized that I was doing 80 mph, much faster than usual. After slowing down to a more reasonable speed, the engine of my beat-up station wagon was still revving strangely. Something wasn’t right. I pulled my foot off the brake and, as an experiment, removed it from the […]

On June 8, 2020, I had a dissociative episode that nearly resulted in suicide. When I say ‘nearly,’ I mean that had I not called a therapist that night, I wouldn’t have been there by the next week. This probably comes as a surprise to many who know me. I’m happy and bubbly and cheerful, […]

I bite my tongue until it bleeds, my stomach turns to knots, and my whole body tenses up. I overthink every step I take, the clothes I wear, my make-up, every person I walk by. Am I going to use the self-checkout or talk to the clerk? What if the self-checkout freezes and I have […]

Here are three things I know for sure: Dealing with Postpartum Depression (PPD) is hard. Watching your partner struggle with clinical depression is hard. Doing both at the same time feels unbearable. Dealing with PPD is Hard I gave birth to my first child on January 16th, 2020. I’m not quite sure I can accurately […]

The World Health Organization recognizes that mental health disorders are the leading cause of illness and disability worldwide. That’s 450 million people suffering from a mental health disorder today. That’s a lot of people! With the Covid-19 pandemic at its peak, the number of diagnosed mental health disorders worldwide is rising daily, as observed by […]

In 2015, I fell off of a cliff. I faced a long recovery from orthopedic and internal injuries, but thankfully, I made it out alive. From gaining strength and mobility to walk again to learning to live with a traumatic brain injury, each step of my healing journey presented a new set of challenges. What […]

Coping is hard. Life gives us problems, and sometimes they’re not really fixable. They remain sore spots for us throughout our lives, even as we grow and change and move on from the old places and things that used to scare us. Too often, we don’t take the time to process and accept the things […]

For people with a history of mental health issues, such as anxiety disorders or depression, isolating during the COVID-19 pandemic can create the perfect storm of worry to cause a crisis. I knew that one of my dearest friends would be experiencing just such a difficult time, and as a friend, I knew I had […]

“Ava, Sophia, and Emma were hanging out again without me. I saw it on their Instagram stories… But that’s ok. I planned to workout today, which means I don’t have time to go anyway.” I wrote in my diary, “Besides, I’m too tired to go socializing with people.” That was two years ago. I was […]

I experienced a happy childhood in many ways. My father was a college professor, and my mother had a medical transcription business at home. I was loved and cared for. Seven years after my birth, my sister Laura came along. She was a joy and a delight to me. I attended a private school, and […]

I stumbled on something random the other day. I was driving in the car, and my negative voices, which I hear often but not constantly, were especially loud. They were telling me to drive my car off the road and that God wanted me dead. I knew that this was not true. I had spent […]

Many people living with a mental illness will hit extreme lows in their lives. They may feel discouraged as they shut themselves off from friends or family, struggle to find work or even refuse all forms of treatment. About one year ago, I hit that low point. I had just moved out of my parents’ […]

Over the last few years, depression has become much more widespread. We’ve all heard it before, “mental health issues don’t discriminate,” and that quote couldn’t be more accurate. Depression impacts people in the suburbs and on farms, in inner cities and refugee camps, in boardrooms and in classrooms. It is estimated that over 300 million […]

The kindest thing I ever heard my father say about me is that I was smart. Really smart. My father never spoke for the sake of being kind. If reality happened to be kind, then so be it. So, when I heard him tell his long-time friend that his daughter, who he scarcely seemed to […]

In recognition of Minority Mental Health Month, for our final blog post of the month, we are featuring a guest post by an African American writer who lives with bipolar disorder. Thank you, Ms. Jordan for your contribution! – Jay Boll, Editor in Chief www.rtor.org You would think going to the psychiatric floor of any […]

You’ll hear this phrase a lot: Your diagnosis doesn’t define you. These aren’t the worst words someone could say to you. In varying forms of ignorance and hurtfulness I’ve been told: You don’t look like you have bipolar disorder That’s a lot to take in I don’t think I can do this These comments and […]

“2:48 am” My body lay still as a doll as I dully gazed at the clock on my desk. My slow, sad, depressing music reverberated and echoed off the walls in my bedroom. I could not sleep. I did not want to get up, move, or feel anything at all. These long restless nights had […]

As early as grade school, I remember struggling to gather up the energy and motivation I needed to get out of bed in the morning and go to school. Some days it was so bad that my mom had to nearly drag me out of bed. I had no problems in school and no real […]

Surviving a mental health crisis isn’t about hospitals and medications that dull your mind and senses. It’s about building a network of people around you to support you and talk with, and to know you well enough to see you’re heading down a bad path, with a lonely road ahead. If you’re lucky, they will […]

“Mood likely and able to change between high and low without warning” – this was written on the keychain charm my mother carried around when I was in my teens. I didn’t understand what bipolar disorder was. I didn’t notice her symptoms, because I simply didn’t know the difference. I’ve always been around mental illness […]

I’m Jo, artist, writer and Renaissance Soul with a potty sense of humor. For over thirty years, I suffered from depression and anxiety, a result of my toxic upbringing followed by post-natal depression. It was a pain in my posterior because I really, really wanted to indulge in my creativity and the Renaissance Soul side […]

“It’s not that bad.” “Others have it worse.” “I’m just being a child.” “I’m not really depressed.” “I’m being ridiculous.” “I’m just a weak person.” “I should be able to handle this myself.” “Why am I being such a baby?” “Stop being stupid.” “Get over it.” Do you hear yourself thinking these things over and […]

Generally, you see “impostor syndrome” in the context of someone’s performance at work. However, in my experience, as well as Fiona Thomas’, it can occur with mental health as well. Even more so, a few Google searches show its application outside of work performance—in relationships, parenting, talent, and then some. One thing that all people […]

Depression. What a loaded word. Not a word I used to let myself say or really think about. A word that used to make me unbearably uncomfortable and filled with shame. A word that people can joke about and may not completely understand. Ten letters that convey so much. Depression. Depression and I were not […]

We met on Tinder. His profile said he was a wildland firefighter, and one of his photos was of him covered in soot and ash with brilliant flames engulfing a forest behind him. I was completely infatuated without ever having met him. It turns out that he was as charming as he was brave, and […]

Co-occurring disorders, also known as dual diagnosis, refer to the combination of substance abuse and the presence of a mental health disorder. Many individuals who enter treatment for substance abuse are also diagnosed with a co-occurring disorder. Over half of all individuals experiencing drug addiction are also believed to have a co-occurring disorder such as […]

I wake up with the feeling that my head is full of cotton wool. At least, that’s how I describe it. It’s hard to put the feeling into words. Thoughts seem sluggish and disoriented. “You need to get out of bed,” a quiet voice whispers. I glance at the clock. It’s 11 am and well […]

“2:32 am” I stared down at my empty shot glasses. The night was as silent as a graveyard. I stumbled to the edge of the mall rooftop and peered off at the city lights in Chiang Mai, Thailand. I was a 20-year-old college student at the time and I had taken the semester off from […]

I didn’t always care about the way I looked. For most of my childhood, I was more focused on making mud pies and playing with my toys. I don’t think I ever thought much about the way anyone looked, or even the way I looked. All the people I loved were loved for who they […]

Mental illness found me at 19 years old. I was in my second year of university with the world at my fingertips, yet I could not get out of bed. I was ridden with depression, anxiety and horrible mood swings that hung over me like a dark cloud. To escape my situation, I would self […]

A lot of older people say that kids nowadays are coddled and overprotected; shielded from figuring out how to fight their own battles so they can function in a cruel unforgiving world, a world where emotional regulation and conflict resolution skills are essential. I can’t speak for every millennial but in my case, they would […]

“What a drag it is getting old.” When Mick Jagger and Keith Richards penned the opening line to “Mother’s Little Helper” in 1966, they were brash 22-year-olds still not at the top of their game. My father, a Rolling Stones fan from the other side of the generation gap, predicted that turning 30 would be […]

Today, we kick off May Mental Health Awareness Month with a guest blog post from a New York man who found a way back from the pain of a mental health crisis through the exercise of creativity. GH Kleiner describes himself as “an empath who can visualize and draw my thoughts and feelings.” His artwork […]

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is very real. A diagnosis that extends far beyond members of the armed forces who have lived through combat, it affects people all over the world. This frequently misunderstood diagnosis, which often goes hand-in-hand with depression, does not have to instill fear, but can actually be an opportunity to embolden survivors. […]

The following recovery story comes from Sallie Crotty who writes about her own experiences with a mental health disorder. Sallie takes us on a journey from her first day to her last day at the Menninger Clinic and what she learned about herself and mental health recovery in the process. We are grateful to Sallie […]

The following story of recovery and hope comes from Alex, who has found a creative way to help himself recover from an eating disorder. Alex has started the blog The Recovery Kitchen where he details both his delicious recipes as well as his own journey in recovery. Today’s post details his personal struggles and triumphs with […]

Today’s wellness story comes from Jeff Fink, the founder of Go Fetch Wellness. Jeff’s story demonstrates the amazing impact animals can have on people’s lives and the importance of a holistic approach to mental health. We are grateful to Jeff for sharing his story with us at rtor.org. –Veronique Hoebeke, Associate Editor Suffering, medications, […]

Today’s story reminds us all to be grateful for the blessings in our lives and to have hope for the future when times are hard. This story comes from Tom who used to lived in San Francisco. He experienced the traumatic loss of his mother at an early age followed by homelessness but he still made it out […]

Let me give you an idea of who I am, what type of OCD I have and what exactly I’m doing about it. I have an annoying OCD enemy situated at the forefront of my brain. We have been together for about 8 years on and off, we disagree on everything and I have been […]

The following story is written by 19 year old Salman, a Kenyan refugee who now lives in Omaha, Nebraska. We all know childhood trauma can have a very negative effect on one’s mental health yet Salman has not let the difficulties of his past stop him. Due to Salman’s persistence, positive attitude and desire […]

The following post is written by Drew Osbahr who uses his love of music as a way to recover from anxiety and depression. We are thankful that Drew has let us share his recovery story on rtor.org -Veronique Hoebeke, Associate Editor Hi, my name is Drew and I have been recovering one step at a time from […]

- 1

- 2